Privatized, Precarious, and Pricey: The New Zealand Economic Mess

How Monopoly Power and Rent-Seeking Keep Kiwis Struggling

We Built Modern New Zealand Ourselves

New Zealand once dared to build a fair and modern society with its own hands. We did not rely on foreign capital or private oligarchies to shape our infrastructure or meet our basic needs. Instead, we collectively created powerful public institutions — monopolies, yes, but natural monopolies, providing essential goods and services that no private actor could fairly or efficiently deliver on their own.

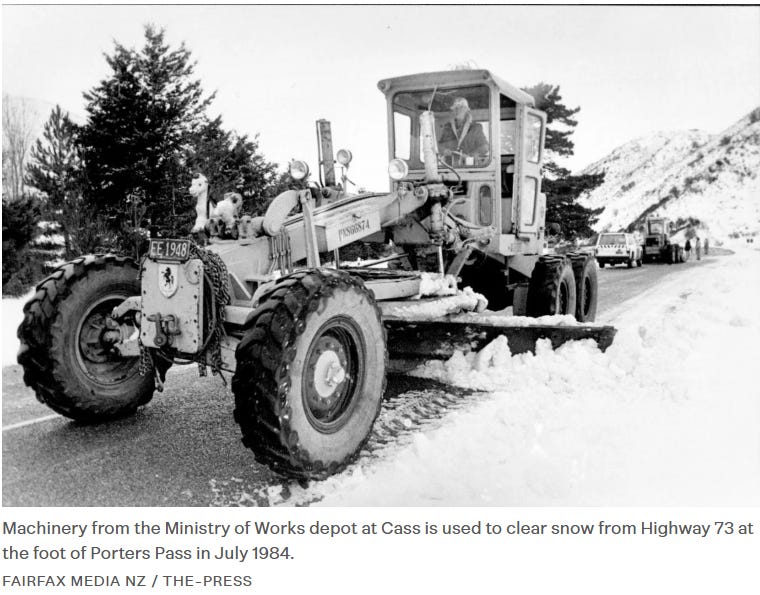

In the early decades of the twentieth century, the government and communities invested together to build railways that connected every corner of the country, electricity systems that reached even the most remote valleys, and a public housing program that gave working families a warm, secure home. The Ministry of Works trained thousands of apprentices while constructing roads, bridges, hospitals, schools, and dams. The Post Office made sure every New Zealander could communicate affordably. State Insurance guaranteed fair, reliable protection against disaster. State marketing boards stabilised farmers’ incomes and maintained quality standards for export produce.

All of these systems were public, accountable, and designed around the principle of universal service. They delivered prosperity, dignity, and economic stability for generations. They also underpinned the growth of secure, well-paid, waged employment — giving workers confidence to build their futures, raise families, and contribute to their communities.

In short, modern New Zealand was built by public ambition. It was not given to us by a benevolent market; it was created by a society with the courage to plan, coordinate, and invest collectively.

The Neoliberal Breakup

That proud tradition of collective ambition was torn apart during the neoliberal revolution of the 1980s and 1990s. Under the banners of “efficiency” and “competition,” successive governments dismantled nearly every one of these public institutions, breaking them up, corporatising them, and selling them off to private owners.

This wasn’t an accident. In 1984, the Fourth Labour Government came to power after a currency crisis, with a group of radical market-liberal ministers — Roger Douglas, Richard Prebble, David Caygill, and their Treasury allies — determined to push through shock reforms. Treasury officials, trained in Chicago-style free-market thinking, provided the intellectual ammunition, while business lobby groups applauded. These policy-makers argued that public monopolies were inefficient and that the private sector would bring innovation and lower costs, ignoring the critical social functions those monopolies had served.

Resistance was widespread. Trade unions tried to defend worker protections. Many public servants fought to preserve their departments. Even community groups and ordinary citizens protested, concerned about losing public services they had relied on for decades. But the pace of change was breathtaking. By using crisis rhetoric — claims that the country was “on the verge of bankruptcy” — the government swept aside opposition. Political tactics included introducing reforms at high speed, splitting up state entities before opposition could coordinate, and portraying any dissent as backward-looking or ignorant.

New Zealand Railways was corporatised and sold to private investors who stripped its assets and ran down its services. The vast hydroelectric generation network, painstakingly built by earlier generations, was split up and partially privatised, leading to today’s gentailer oligopoly with its endless price hikes. Telecom, a modern communications miracle created by the state, was sold off and rebranded Spark, extracting huge profits from the very infrastructure taxpayers had paid to build.

The Ministry of Works — an institution that had employed thousands and trained the nation’s engineering and trades workforce — was simply abolished, leaving public projects to be outsourced piecemeal to private consultants and contractors. State Insurance was sold to global giants, ending its role as a fair, public alternative. Air New Zealand, the proud national carrier, was part-privatised and forced to prioritise profit above service, only partly renationalised after collapsing — but still run as a commercial operator.

Even state housing was gutted, with building programs slowed to a crawl and responsibility shifted to accommodation supplements — effectively a transfer of taxpayer money into private landlords’ pockets. Ports, airports, and marketing boards were corporatised and forced to act like profit-driven businesses, raising prices while cutting stable jobs.

The result of this wholesale sell-off and commercialisation was predictable. Costs for ordinary people rose. Secure, well-paid employment was replaced by casual, precarious, gig-like work. Coordination disappeared, replaced by a patchwork of private monopolies and duopolies interested only in short-term profit.

What was once a public, universal guarantee of prosperity became a playground for asset-strippers, rentiers, and financiers.

The Cyclical Myth: Why Waiting Won’t Work

A common refrain in New Zealand politics and media is that the economy moves in natural cycles—periods of downturn followed by inevitable recovery. We hear it from politicians, economists, and commentators alike: the economy is “at the bottom of the cycle” and things will soon pick up again. This idea reassures many who are struggling with unemployment, stagnant wages, and rising living costs.

But this cyclical narrative ignores a crucial reality: since the neoliberal reforms of the 1980s and 1990s, New Zealand’s economy is not simply fluctuating around a healthy equilibrium. Instead, it has been structurally reshaped in ways that trap workers, renters, and small businesses in precarity.

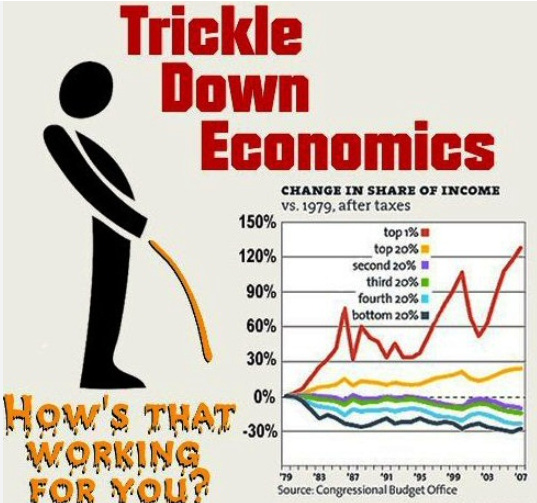

Economic “booms” over the last few decades have often been driven not by productive investment but by asset speculation, particularly in property. The “growth” we see is inflated by rising land and housing prices, supermarket duopolies, and monopolistic control of essential goods and services. Meanwhile, wages remain low, job security declines, and public infrastructure crumbles.

The consequence is that waiting for the “cycle” to turn is like waiting for a tide to lift a boat with a large hole in the hull. Without fixing the structural problems—the fragmentation of public services, the dominance of rentier interests, the lack of secure work—any cyclical recovery will be shallow and short-lived, benefiting primarily the wealthy owners of assets rather than ordinary people.

The Politics of Rentier Protection

The National Party’s latest flagship policy — encouraging a backyard “granny flat boom” — is marketed as a compassionate solution: a way to house more people while creating work for tradespeople whose pipelines have dried up. It sounds plausible, especially when repeated across talkback radio and sympathetic media. But this narrative is deeply misleading.

First, these scattered backyard builds do not actually generate secure, sustained employment. Unlike large-scale state housing projects that can guarantee work for hundreds of tradespeople and apprentices over years, granny flats are usually one-off jobs, short-term, and often awarded to a handful of well-connected contractors. There is no reliable pipeline of training, secure wages, or career progression. Once a backyard flat is done, the work vanishes.

Second, National’s real goal is not to fix the housing shortage, but to protect high house prices. Large-scale, coordinated public housing construction — which Kainga Ora was beginning to deliver — would eventually lower average prices by providing a real alternative to the private rental market. That would directly threaten the phantom equity on which many of National’s voter base depends.

By shutting down and gutting Kainga Ora’s ambitious building program, National is deliberately reintroducing scarcity back into the housing system. Then, with their granny flat scheme, they funnel what little public support remains into backyard intensification. This means no new land is brought into the market; no downward pressure is placed on land prices; the current property-owning class can rest easy knowing their paper gains will remain intact.

The biggest beneficiaries of this “granny flat bonanza” will not be tradies or renters — they will be the same entrenched monopolies who have dominated the building materials sector for decades. Fletcher Building and other near-cartel players, who have long profited from their hold over plasterboard, timber, and concrete, stand to gain most. Many of these businesses are significant donors or ideological allies of the National Party, and the policy looks suspiciously like it was designed to keep their order books and shareholder returns healthy, even as the housing crisis festers.

It is easy to sell the granny flat narrative to an electorate conditioned by conservative media to believe that any building is automatically good building. But if you look closely, the scheme delivers neither affordability nor secure, skilled employment, nor a genuine structural fix. It is little more than a protective moat for the rentier class, dressed up as a helping hand to homeowners.

New Zealand deserves better than a piecemeal policy designed to protect private equity at the expense of people who need truly affordable, secure homes.

Short-Term Thinking, Long-Term Damage

The pattern of short-term fixes and rentier protection we see in policies like the granny flat push stands in stark contrast to the approach taken by many Scandinavian and Central European countries. These nations have deliberately built economies centered on secure, well-paid waged employment, robust social safety nets including pensions and universal healthcare, affordable and accessible housing, and comprehensive childcare systems.

In places like Sweden, Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands, governments invest heavily in public infrastructure and social services, ensuring citizens enjoy a high quality of life while sustaining long-term productivity. Secure jobs supported by strong unions and collective bargaining are the norm, not the exception. Housing markets are actively managed to keep prices affordable, preventing the kind of speculative bubbles that dominate New Zealand’s property scene.

By contrast, New Zealand’s prevailing economic model prioritizes short-term “activity” — often in the form of asset speculation and rent extraction — over these foundational elements of social and economic stability. The result is a deteriorated economy marked by widespread precarious work, insecure housing, minimal childcare support, and growing inequality.

Until we shift away from managing cyclical ups and downs and confront the structural flaws of our economy, New Zealand will continue to lag behind nations that have chosen to invest in durable, equitable growth. Genuine economic health means creating an environment where all people can access secure work, stable homes, and essential services — not just protecting the profits of rentiers and monopolies.

Why the Right Chooses Rentier Favours Over Real Investment

It’s worth asking: why do right-wing politicians in New Zealand so eagerly funnel public money to the rentier class—the landlords, property developers, building materials cartels, supermarket duopolies, and power gentailers—while their counterparts in Scandinavian and many European countries prioritize investment in productive sectors and social infrastructure?

The answer lies partly in ideology but mostly in political expediency, class loyalty, and a perpetuation of low social investment that suppresses productivity. New Zealand’s conservative politicians have aligned themselves closely with a narrow elite whose wealth depends on extracting unearned income from property speculation, monopoly rents, and controlled markets. This rentier class forms a reliable political base that funds campaigns, shapes media narratives, and influences policy decisions. Protecting their phantom wealth is the overriding priority.

In contrast, countries like Sweden, Denmark, and Germany invest heavily in social spending on free education, vocational training, early childhood care, and healthcare. These investments build human capital, improve literacy—both basic and civic—and promote political and economic understanding among their citizens. This in turn boosts productivity and innovation, creating a virtuous cycle of shared prosperity and sustainable growth.

New Zealand, however, has historically underfunded these crucial areas. Literacy rates, civic knowledge, and economic understanding lag behind peer countries. The consequence is a workforce less equipped for high-productivity roles, more vulnerable to economic shifts, and less able to advocate effectively for systemic reform.

Low productivity also plays into financial policy. Because productivity growth is weak, interest rates remain artificially low to stimulate borrowing and spending. But these low rates disproportionately benefit the rentier class, who rely on cheap capital to expand property portfolios and dominate monopolistic markets. In effect, the political and economic elite benefit from a low-productivity trap: keeping the workforce under-skilled and the economy skewed toward asset speculation ensures continued demand for cheap credit, inflating asset bubbles that enrich landlords and financiers.

This dynamic is self-reinforcing. By maintaining low investment in education and social infrastructure, right-wing politicians sustain a social and economic environment that keeps productive growth low and rentier profits high. Their political survival depends on preserving this status quo—funding key donors, winning media support, and suppressing the civic literacy necessary for a meaningful challenge to their rule.

The result is not just a failure of imagination or policy but a deliberate strategy: sacrifice long-term social and economic health to protect entrenched private interests. This is why New Zealand continues to suffer from stagnant productivity, precarious employment, and widening inequality—all while the rentier class enjoys inflated wealth and political influence.

A Path Forward

New Zealand’s story need not end with entrenched inequality, precarious work, and an economy rigged for rentiers. We have seen before what collective ambition and public investment can achieve. It is time to reclaim that vision.

But any serious transformation must also confront the media landscape that shapes public discourse. New Zealand’s media ecosystem is overwhelmingly right-wing or centrist, dominated by talentless, privileged middle-class insiders whose families expect to pass down phantom equity, grooming the next generation to become rentiers themselves. It’s the old Prince Charles problem, playing out in a small, complacent society.

These media gatekeepers produce lowest-common-denominator content — shows like Seven Sharp — that anesthetize the public, dulling critical thought and stifling the irreverence that should energize democracy. Instead of provoking the kind of joyous rebellion against mediocrity and entrenched privilege that a healthy society needs, they reinforce complacency.

Behind their bland façades, these privileged storytellers quietly fear the coming reckoning — the inevitable moment when the next generation recognizes the rot beneath the surface, pops the speculative bubbles, and drives out the parasites who have feasted too long. Until then, they cling to their cushy platforms, spinning narratives that protect their own class interests and discourage meaningful challenge.

To build a better New Zealand, we need not only bold economic and social reform but a media ecosystem that empowers citizens, challenges power, and nurtures civic literacy. When people are informed, engaged, and unafraid to call out mediocrity and injustice, political will shifts, and meaningful change becomes possible.

The journey won’t be easy, but it is necessary. For too long, the promise of “nice things” has been deferred, sacrificed at the altar of rentier privilege and talentless complacency. By recognizing what we have lost and committing to rebuild from first principles — in both our economy and our public discourse — New Zealand can create a future where security, fairness, and opportunity are realities for all.

It’s Time to Stop Playing Along

The politicians and institutional gatekeepers holding New Zealand back are shockingly talentless. They’re a complacent, privileged bunch, recycling the same hollow talking points and safe ideas because they’ve never been seriously challenged. They’re counting on us to stay quiet, to keep tuning in to their bland shows, to keep accepting the scraps from their rentier banquet.

But here’s the truth: it wouldn’t take much to dislodge them. We don’t need genius or armies; we just need to get up and scare the shit out of these complacent, out-of-touch careerists. Their grip depends on public passivity — and that’s their biggest weakness. Once people start calling them out, demanding real change, and refusing to be placated with token gestures and hollow promises, the whole house of cards would wobble.

It’s easier than they want you to believe. They live in fear of the next generation who will see through their lies and their phantom equity bubble. But it’s up to us to light the fuse.

So don’t sit back. Don’t buy their spin. Don’t let these talentless gatekeepers and self-serving politicians keep running the show. Make noise. Demand better. Be the disruption they never saw coming.

Because if we don’t, someone else will — and when they do, the reckoning won’t just rattle the system; it will tear it down.